Dismissal increases occupation change probability eleven-fold, with significant financial and career consequences, shows study

The loss of your job can be as devastating emotionally as a divorce. It’s true that a divorce can actually enhance your marriage skills for the next time around, since the skills needed remain virtually unchanged, but the same cannot be said for job-loss situations. Following a dismissal, skills previously used can become obsolete or degraded, particularly if the jobless period drags on, resulting in a mismatch between your personal skill sets and the market demands.

Who is most affected by this skill mismatch? What is the magnitude of the effect? In what ways does it translate into lost earnings? A study recently published in the journal Research Policy put numbers to these questions.

“Our study reveals that the consequences of job displacement extend far beyond immediate job loss. The type and direction of skill mismatch in post-displacement occupations significantly impact workers’ earnings trajectories over time,” says Ljubica Nedelkoska from the Complexity Science Hub (CSH).

“Understanding these dynamics is crucial for policymakers and employers seeking to support displaced workers in navigating career transitions,” adds Nedelkoska, who is one of the authors of the study along with Frank Neffke, from CSH, and Simon Wiederhold, from the Halle Institute for Economic Research.

GERMAN LABOR MARKET

The researchers examined the work history of displaced German workers between 1975 and 2010 who lost their jobs for reasons unrelated to their performance, such as establishment closures – representing roughly 1.6 million workers in total. They found significant heterogeneity in earning losses, ranging from 4% to 16.5% ten years after displacement, compared to what they would have earned had they kept their jobs.

Nedelkoska and her colleagues hoped to uncover the reasons behind this heterogeneity. Their next step, then, was to combine information about the task content, education and training for 263 occupations from a representative survey of more than 20,000 German employees, with the employment histories of a 2% longitudinal sample of German workers drawn from social security records.

EXPECTED, BUT ALSO SURPRISING

As expected, the researchers found out that, during periods of economic growth, workers moved more often to more demanding jobs requiring new skills. They also observed that, during recessions, the opposite occurred. It was also unsurprising to Nedelkoska and her colleagues that younger workers were more likely to move to more demanding jobs than their older counterparts.

There was, however, one finding that surprised the researchers. The magnitude of occupation-switching among displaced workers was 11 to 12 times higher than among observationally identical non-displaced workers.

STAYERS AND SWITCHERS

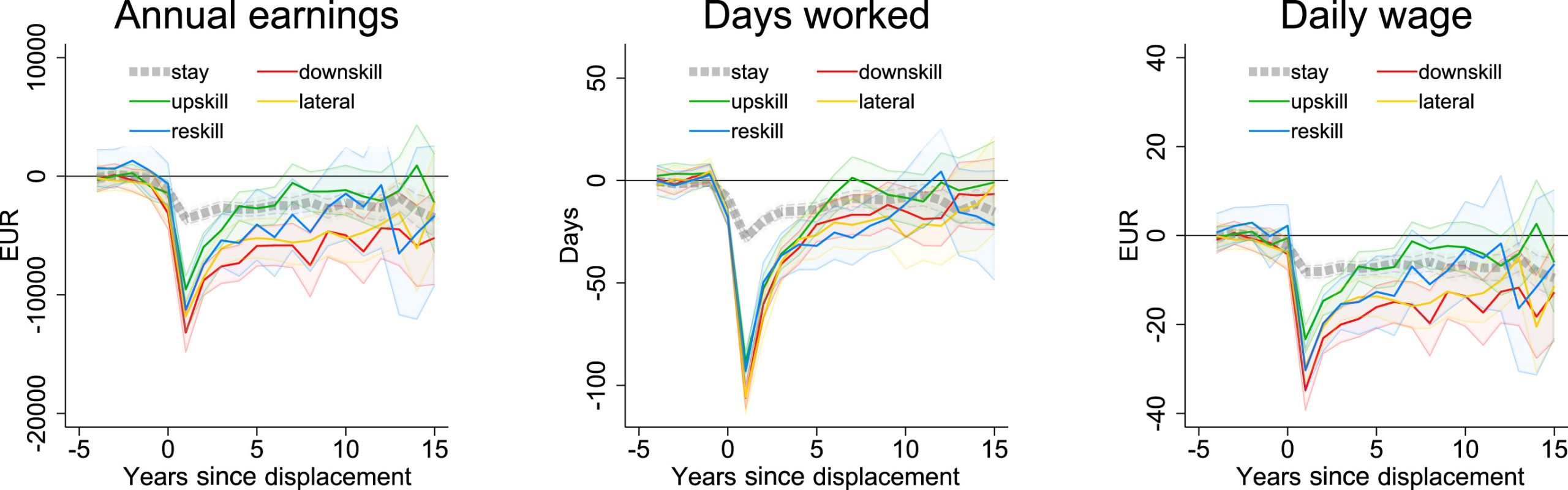

In order to better understand this occupation-switching, the researchers divided the displaced workers into five groups: stayers (those who find jobs in the same occupation); upskillers (many new skills required and few skills made obsolete), downskillers (few new skills required and many skills made obsolete), reskillers (many new skills required and many made obsolete), and lateral switchers (different occupation but more or less the same skills).

Nedelkoska and colleagues found that switchers suffered significantly larger displacement-related earnings losses than stayers. According to the analysis, 15 years after displacement, switchers still earned 16.5% less than if they had continued their old occupation, whereas, for stayers, losses were limited to 8.7%.

“It is interesting – but also sad – to note that, while most displaced switchers either skill down (35%) or up (36%) after displacement, the downskilling sort earned on average 22.4% below their pre-displacement wages, compared to 8.9% for the upskilling sort,” highlights Nedelkoska, who’s also a researcher at the Growth Lab at Harvard University.

Additionally, upskilling switchers were able to catch up to their counterfactual wage curves within seven years, while downskilling switchers remained behind their counterfactual wage curves 15 years after being displaced. However, few upskillers manage to outperform occupation-stayers.

SKILL MISMATCH

The findings point to skill mismatch as a determining factor, according to the researchers. The greatest losses were suffered by workers who chose new jobs in which many of the skills they used in their previous occupations did not apply. Those who moved to jobs that required more skills than their pre-displacement occupation experienced the mildest losses.

It is important for policymakers and companies to assist workers in adapting to changing labor market demands, add the authors of the study. “Our findings emphasize the importance of avoiding skill mismatch, and in particular, downskilling, which imposes the largest and most persistent costs on workers,” point out Nedelkoska and colleagues. A number of solutions could be offered, such as providing continuous retraining throughout a person’s career, which can be enabled through personal learning accounts; enabling central employment agencies to give frequent career counseling; or encouraging geographic mobility.

About the study

The study “Skill mismatch and the costs of job displacement,” by Frank Neffke, Ljubica Nedelkoska, and Simon Wiederhold has been published in Research Policy (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104933)

This text is based on a press release from the Ifo Institute’s Pillars Team.