SIMULATION MODEL SHOWS HOW A SAFE OPERATION IS POSSIBLE

Developed during the ongoing pandemic, but adaptable to various needs: Hub scientists developed a simulation model for keeping schools open safely during a surging pandemic.

It was a hot topic of discussion about a year ago: is it irresponsible to send children to school, or can schools be reopened safely if enough prevention measures are in place?

A research team at the Hub wanted to add evidence to the debate. Jana Lasser, then working in Peter Klimek‘s team and now a scientist at Graz University of Technology, developed a school simulation model that shows how and how likely the virus spreads in different school settings. The model also allows to calculate how effectively (bundles of) measures can prevent this spread.

For this study, published in the current issue of Nature Communications, the CSH team modeled the delta virus variant, which was the predominant variant in Austria until before Christmas. “However, we can adapt our model any time and simulate a wide variety of other scenarios,” says the complexity scientist and first author of the paper.

The research team developed and calibrated the “school tool” with data on 616 corona clusters that had occurred in Austrian schools in the fall of 2020. The anonymized data were contributed by the Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety (AGES).

To get a sense of what measures could realistically be implemented in schools, the researchers also conducted several interviews with school principals and teachers.

THE MULTITUDE OF POSSIBILITIES MAKES THE UNDERTAKING COMPLEX

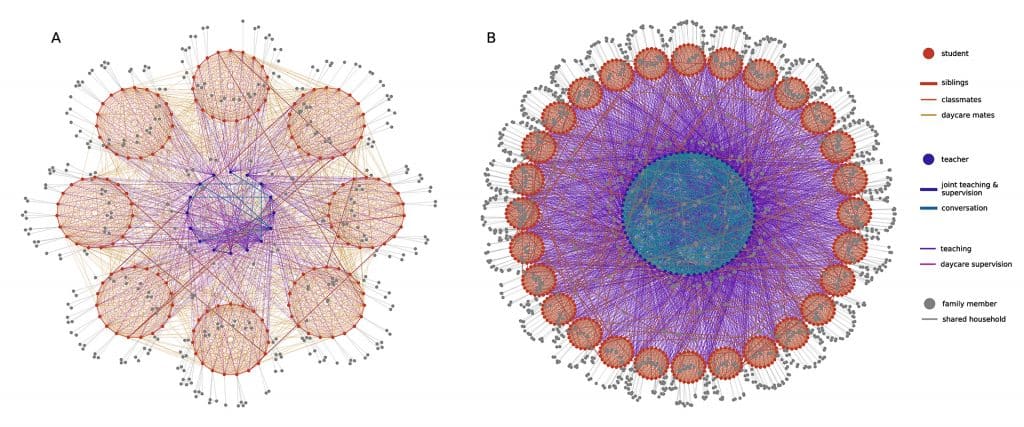

First, the scientists defined different types of schools: How many classes does a school have, how big are the classes and how many teachers are there at the school? “In our model, we distinguish primary schools with or without afternoon daycare, lower secondary schools with or without afternoon daycare, upper secondary schools, and secondary schools with children from the age of 10 to about 18,” Lasser says.

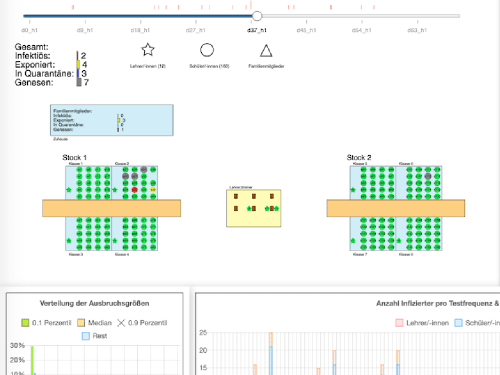

These virtual schools can implement different measures to prevent infection spread. The measures include: wearing masks, frequent intensive ventilation of classrooms, regular testing of children and teachers, and class size reduction. The scientists also simulated different vaccination rates among teachers and children.

IMG.: THE CONTACT NETWORKS IN A PRIMARY AND A SECONDARY SCHOOL

IT’S ALL ABOUT THE MIX

One major result of the work is that the measures must be adapted to the different types of schools. “Secondary schools tend to be larger, with more children in each class and changing teachers. Therefor there are significantly more opportunities for an infection to spread—the web-based visualization we also developed for the simulation tool nicely shows how an infection propagates through a school,” Jana explains.

This higher risk of large outbreaks in bigger schools means they need to implement more measures than elementary schools.

Based on the delta variant and given that 80 percent of the teachers are vaccinated, the model shows that elementary and lower secondary schools can keep the reproduction rate R below 1 (i.e., one sick person infects less than one other person, on average) with classroom ventilation, wearing masks, and class size reduction even when children are not vaccinated.

In all other types of schools, the same measures can help to keep R<1 —and thus (re)open relatively safely—if half of the children are also vaccinated.

In larger schools, testing should also focus on teachers as a possible source of infection, since they have many more contacts throughout the day and can carry the virus to different classes, the researchers point out.

SWISS CHEESE

“We clearly see the effectiveness of the so-called Swiss cheese model,” explains Peter. “No single measure alone can protect one hundred percent, but with several measures combined, protection increases considerably.”

“In addition, the correct implementation of measures is of extreme importance,” he continues. “Even a small deviation—for example, if classes are ventilated less frequently or not all children are getting tested—is enough to make cluster sizes grow exponentially.”

Of all individual interventions except for vaccination, the ventilation of classrooms is most effective in preventing a cluster—as long as windows are consistently opened for five minutes every 45 minutes. Also highly effective is testing of students and teachers two to three times a week; antigen testing was used in the model.

OMICRON CHANGES THE RULES OF THE GAME

Well—that was all true for delta. But what about the much more contagious Omicron variant?

“Since Omicron has become dominant in Austria, I was really interested to see what our simulations would show for this highly transmissible variant,” says Jana. “My results, although of course not yet peer-reviewed, show that due to the much higher infectiousness of Omicron, we need all available measures in all types of schools to prevent larger outbreaks in schools. Only elementary schools can omit one measure while still controlling outbreaks, such as splitting classes.”

For those who want to do their own math, the simulation code can be freely downloaded from the web, Peter adds. “Good coders could even tailor the model to their own needs. The relevant numbers, such as the infectiousness of a disease, number of classes, children and teachers, or the individual measures to prevent disease spread, can all be adjusted.”

VISUALIZATION HELPS TO PERSUADE

Jana—who always also thinks in terms of science communication— also emphasizes the value of a well-done visualization of the model as an educational resource for parents, children, school leaders or authorities. “It is always impressive to see how quickly a virus spreads in a group, and how infection dynamics change when single or multiple measures are introduced. Good visualizations can do a great deal to help people understand the necessity of these sometimes uncomfortable measures,” she concludes.