New study challenges conventional method for measuring homophily and proposes a novel approach

It is likely that you have heard of the term homophily before. After all, the concept permeates all of our relationships, both in real-life and online – the way we make friends, the way we choose a sexual partner, who we follow on social media, or who we collaborate with if we are artists or scientists. It is the idea that people who are alike act alike, that “birds of a feather naturally flock together,” that similarity breeds connection.

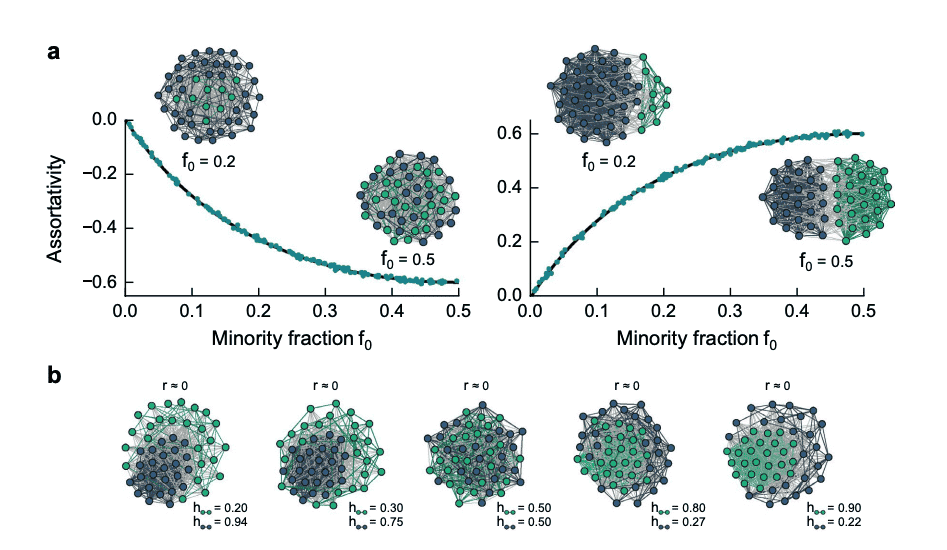

In order to identify homophilic tendencies in social networks, scientists have mostly relied on one method to examine how groups interact in a variety of social settings. It is the nominal assortativity method, a widely used metric known for characterizing mixing patterns in networks based on categorical attributes like gender, ethnicity, or social class. Now, a recent paper published in Scientific Reports demonstrates that the conventional approach has shortcomings and may produce misleading results.

“We show that nominal assortativity fails to assess homophily accurately in certain scenarios,” say Fariba Karimi from the Complexity Science Hub (CSH) together with Marcos Oliveira from the University of Exeter. “Despite its popularity and relative accuracy in capturing homophily in a variety of networks, nominal assortativity can produce distorted assessments of mixing patterns in networks with unequal groups and asymmetric mixing.”

NARRATIVE CHANGE

According to Karimi, their findings could have a significant impact on how researchers study social networks, offering a more nuanced understanding of how different groups interact. “Our research may change the narrative of how we study homophily.”

“Accurately measuring biases within group interactions is crucial for understanding the dynamics of social networks. These biases greatly impact perceptions of minority groups, their access to social capital, and even influence their algorithmic visibility,” points out Karimi, who leads CSH’s computational social science group. “Our research introduces a novel approach to accurately evaluate assortativity that can be applied to a wide range of networks,” adds Karimi, who’s also a professor of data science at Graz University of Technology.

REAL-LIFE EXAMPLES

In the study, Karimi and Oliveira conducted extensive analyses using synthetic and real-world networks. “Looking at real collaboration networks, we found that networks that were considered ‘neutral’ – meaning there was no indication of homophilic behavior – when using nominal assortativity weren’t neutral after adjusting the method,” explains Karimi. One example is the developer platform GitHub, with over 100 million users, of which only 6% are women. In follower-followee relationships, nominal assortativity did not show positive homophily – that is, men do not gravitate toward only men. The adjusted nominal assortativity, however, did indicate positive gender homophily tendencies.

UNEQUAL GROUPS AND ASYMMETRIC MIXING

According to the authors, real-world networks often feature unequal group sizes, with some significantly smaller than the largest group. This scenario is evident in STEM fields, such as computer science and physics, where women are a minority within professional networks.

As Karimi and Oliveira point out, considering these varying group sizes is crucial for estimating potential structural biases in how different groups interact. The authors also argue that networks might display asymmetries in the way groups interact.

“For example, in male-dominated scientific fields, established researchers could be primarily men due to historical first-mover advantages. Thus, senior men have the resources to drive their collaboration network, implying that the tendency for male-male collaboration may not be the same as female-female collaboration. In such settings, homophily is asymmetric, having different strengths for the minority and majority groups. These asymmetries, however, are lost when using a single-valued measure to characterize group mixing, such as nominal assortativity,” illustrate the authors.

ADJUSTED METHOD

To address these limitations of nominal assortativity, the study proposes an adjusted method that effectively rectifies the group-size imbalance issue and accurately recovers expected assortativity in networks. “Using a more accurate approach, which takes into account group sizes as well as asymmetries in networks, we can attain a heightened comprehension of the mechanisms governing our social lives,” says Karimi.

“By accurately assessing interactions among groups, we gain valuable insights into the impact of homophily on minorities, which lays the groundwork to uncover potential causal loops between the sizes of these groups and their mixing dynamics,” adds Oliveira.

The study “On the inadequacy of nominal assortativity for assessing homophily in networks,” by Fariba Karimi and Marcos Oliveira, was published in the latest issue of Scientific Reports.

About the study

The study “On the inadequacy of nominal assortativity for assessing homophily in networks,” by Fariba Karimi and Marcos Oliveira, was published in the latest issue of Scientific Reports.